Clinico-epidemiological profile of snake bite in children in a tertiary care hospital, South India

Abstract

Introduction: A high incidence of snake bite envenomation is observed in India, due to rapid urbanization and deforestation. Snake bite is a life-threatening conditionand remains a significant cause for hospital admissions in paediatric age group. Because of their smaller body mass, they have rapid systemic envenomation and high mortality rate.

Methods: This is a descriptive type of study about clinical and epidemiological profile of snake bite cases in pediatric age group and also included unknown bites with features of snake bite envenomation. This was done for the period of one year from July 2015 to June 2016. Data about age, sex, bitesite, clinical features, complications, management and outcome were collected and analysed.

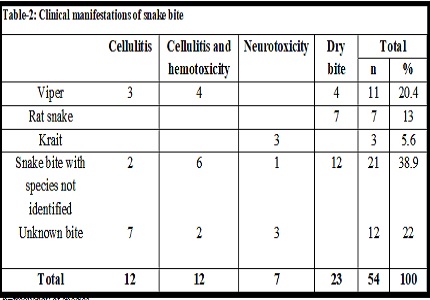

Results: The study included 54 cases of snake bite victim. Majority were boys (64.8%). The common age group affected was 5-10 years (59%). Lower extremities were the most common site of bites (85%). 42.6% of cases had clinical features within 2 to 6 hours of snake bite. Bite admission interval was 6 hours. Prehospital treatment was employed in 10.3% of patients. In our study, 38.9 % of victimspresented with snake bite of unknown species, 39% known species of snakes and 22.1%were cases of envenomation, where the snake was not visualized. The commonest identified species were viper bite (n=11, 20.4%), followed by rat snake (n=7, 13%) and krait (n=3,5.6%).23(42.6%) cases had dry bite. About 12 (22%) children had local cellulitis; 12 (22%) had combined cellulitis and hemotoxicity; 7 (13%) had neurotoxicity. In our study polyvalent Anti snake venom (ASV) was used in 55.6% of cases and 18.5% of victims developed hypersensitivity reactions to ASV.The case fatality was 11.1% and Krait was the main cause of mortality.

Conclusions: Of the children presented with snake bite envenomation, the snake was visualized in majority of cases. Most of them developed clinical features in 2 to 6 hours ofbite. Cellulitis was the commonest presentation and polyvalent ASV was used for treatment. Neurotoxic Krait bite was the commonest cause of mortality.

Downloads

References

2. National snakebite management protocol, India. (2008). [online] Available at www://mohfw.nic.in (Directorate General of Health and Family Welfare,/Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India).

3. Chippaux JP. Snake-bites: appraisal of the global situation. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76(5):515-24. [PubMed]

4. Central Bureau of Health intelligence-India. National Health Profile (NHP) of India-2011. Health status indicators. Cases and deaths due to snakebites in India. Retrieved from cbhidghs.nic.in/index1.asp

5. Mohapatra B, Warrell DA, Suraweera W, Bhatia P, Dhingra N, Jotkar RM, Rodriguez PS, Mishra K, Whitaker R, Jha P; Million Death Study Collaborators. Snakebitemortality in India: a nationally representative mortality survey. PLoSNegl Trop Dis.2011 Apr 12;5(4):e1018. doi: 10.1371/journal. pntd.0001018. [PubMed]

6. Warrell DA. Snake bite: A neglected problem in twenty-first century India. Natl Med J India. 2011;24:321–4. [PubMed]

7. Warrell DA, Gutiérrez JM, Calvete JJ, et al. New approaches and technologies of venomics to meet the challenge of human envenoming by snake-bites in India. Indian.J Med Res 2013;138:38-59. [PubMed]

8. World Health Organization (2007). Rabies and Envenomings. A Neglected Public Health Issue: Report of a Consultative Meeting. Geneva: WHO.

9. Warrell DA. WHO/SEARO guidelines for the clinical management of snakebite in the Southeast Asian region. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999;30:1–85. [PubMed]

10. Morais V, Massaldi H. Economic evaluation of snake antivenom production in the public system. J Venom Anim Toxins incl Trop Dis. 2006;12(3):497-511.

11. Kasturiratne A, Wickremasinghe AR,de Silva N, et al. The global burden of snakebite: a literature analysis and modeling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med.2008:5(11):e218. [PubMed]

12. Kshirsagar VY, Ahmed M, Colaco SM. Clinical Profile of Snake Bite in Children in Rural India. Iranian J Pediatrics. 2013;23(6):632-6.

13. Mead HJ, Jelinek GA. Suspected snakebite in children: a study of 156 patients over 10 years. Med J Aust. 1996 Apr 15;164(8):467-70. [PubMed]

14. Karunanayake RK, Dissanayake DMR, Karunanayake AL. A study of snake bite among children presenting to a paediatric ward in the main Teaching Hospital of North Central Province of Sri Lanka. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:482.

15. Aktar F, Aktar S, Yolbas I, Tekin R. Evaluation of Risk Factors and Follow-Up Criteria for Severity of Snakebite in Children. Iran J Pediatr. 2016 Jul 10;26(4):e5212. eCollection 2016 Aug.

16. Kulkarni ML, Anees S. Snake venom poisoning: experience with 633 cases. Indian Pediatr. 1994 Oct;31 (10):1239-43.

17. Sankar J, Nabeel R, Sankar MJ, Priyambada L, Mahadevan S (2013) Factors affecting outcome in children with snake envenomation: a prospective observational study. Arch Dis Child 98: 596–601. doi: 10.1136/ archdischild-2012-303025. [PubMed]

18. Adhisivam B, Mahadevan S. Snakebite envenomation in India: a rural medical emergency. Indian Pediatr. 2006 Jun;43(6):553-4. [PubMed]

19. Gautam P, Sharma N, Sharma M, Choudhary S. Clinical and demographic profile of snake envenomation in Himachal Pradesh, India. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:934–5.

20. Ariaratnam CA, Thuraisingam V, Kularatne SA, Sheriff MH, Theakston RD, de Silva A, Warrell DA. Frequent and potentiallyfatalenvenoming by hump-nosedpit vipers (Hypnalehypnale and H. nepa) in Sri Lanka: lack of effectiveantivenom. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.2008 Nov;102(11):1120-6. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008. 03.023. Epub2008 May 2.

21. Seneviratne SL, Opanayaka CJ, Ratnayake NS, Kumara KE, Sugathadasa AM, Weerasuriya N, Wickrama WA, Gunatilake SB, de Silva HJ. Use of antivenomserum in snake bite: a prospective study of hospital practice in the Gampahadistrict.Ceylon Med J.2000 Jun;45(2):65-8.

22. Alirol E, Sharma SK, Bawaskar HS, Kuch U, Chappuis F (2010) Snake Bite in South Asia: AReview. PLo SNegl TropDis4(1):e603.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000603

Copyright (c) 2018 Author (s). Published by Siddharth Health Research and Social Welfare Society

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

OAI - Open Archives Initiative

OAI - Open Archives Initiative